We at the blog wish everyone a Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays!

Your Resource for the Tate-LaBianca (TLB) Murders

Yesterday :: Today :: Tomorrow :: Where No Sense Makes Sense

Monday, December 25, 2023

Thursday, December 21, 2023

The Never-Ending Story Alta Magazine

This article was published by Alta magazine.

The Never-Ending Story

Former Manson family member Bruce Davis is one of more than a hundred high-profile California lifers who face repeated parole denials and gubernatorial reversals.

JOE GARCIA AND KATE MCQUEEN

PUBLISHED: DEC 21, 2023

Editor’s note: This is a co-authored article. Incarcerated journalist Joe Garcia reported from inside San Quentin State Prison; free-world writer Kate McQueen interviewed sources and wrangled documents on the outside. Garcia serves as the article’s narrator, but the writing itself was a joint effort, with both authors touching all parts of the text.

When Bruce Davis stepped off a transfer bus at San Quentin State Prison in 2019, the news of his arrival spread quickly through the incarcerated community. A Manson family member now lived among us. Helter skelter. Swastikas carved into foreheads. Fanatical female cultism. All the hype surrounding Charles Manson still had pull 50 years after the fact, even here.

As an incarcerated journalist, I’ll admit my curiosity was triggered too. How many reporters can say they walk the yard or sit down to breakfast with the person sometimes referred to as Manson’s right-hand man? Though not involved in the famously gruesome killing of Hollywood star Sharon Tate, Davis was found guilty of two other 1969 Manson family murders, of musician Gary Hinman and stunt person Donald “Shorty” Shea. I approached Davis with aspirations of delving inside the mind of a famous killer.

What I found instead was altogether more shocking to me. Our frequent conversations revealed a humble, contrite, down-to-earth old man who had confronted his demons long ago and spent decades working to resolve the dark implications of his own criminal acts. Davis is 81 years old, a born-again Christian whose soft speech is often broken by coughs from emphysema. When he arrived at San Quentin, he moved as if he were made of glass, one fully replaced hip slowed by another badly in need of repair. It’s hard to imagine anyone feeling scared by him today.

California’s Board of Parole Hearings had also seen what I witnessed. The board had found Davis suitable for parole right before his transfer to San Quentin. It was his 32nd parole hearing and the sixth consecutive time that the BPH decided he was not a threat to public safety.

Parole is the conditional release that rounds out an indeterminate “life term” prison sentence like Davis’s, and like mine. I’ve been incarcerated since 2003, when I shot and killed a fellow drug dealer. And like Davis, in the years since my sentencing, I’ve spent countless hours working to understand what led me to commit my crime and preparing for life outside the walls.

In exchange for this type of rehabilitative effort, parole is, in theory, a promise that a lifer may earn their freedom after they’ve served their minimum term. In practice, it is a system that transfers the decisions about release out of the hands of a judge and into the hands of a governor-appointed board that operates with considerable latitude. And in addition to the BPH, lifers in California face another hurdle, the gubernatorial veto, a privilege that only one other state—Oklahoma—permits. Before Davis’s transfer, then–newly inaugurated governor Gavin Newsom reversed the board’s recommendation, becoming the third consecutive governor to deny Davis release.

Newsom’s decision surprised none of the outside journalists I spoke to. Nikki Meredith, a retired Bay Area journalist and the author of The Manson Women and Me: Monsters, Morality, and Murder, figured that letting any of the Manson family members go was a risk that verged on political suicide.

William J. Drummond and John C. Eagan, two other veteran reporters, said the same thing when I expressed concern about Davis’s situation. Drummond recalled how his Los Angeles Times front-page story on a crashed plane at the California-Nevada border was bumped to below the fold when the news of the Tate-LaBianca murders broke. That kind of crime, when it happens, eclipses all other news.

It’s a tough balancing act to take seriously the damages caused by crimes and also make it possible for people guilty of crimes to eventually go home. It’s also the law. California has had a parole system since 1893. In 2005, the state legislature reemphasized California’s long-standing commitment to parole by renaming the Board of Prison Terms as the Board of Parole Hearings, expanding the hearing board, and adding the last two words to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation name. The state’s parole statutes stipulate that parole “shall normally” be granted. But what rehabilitation actually means, the legislature hasn’t defined.

Today, about 33,000 people are serving life sentences in California state prisons. Lifers like Davis, who face repeated parole denials and gubernatorial reversals, are the ultimate stress test for the state’s justice system—one invested in more than retribution. For these high-profile lifers, achieving their physical release from prison requires them to be not only rehabilitated but also freed from the aura surrounding an infamous crime.

In order for that to happen, another story, one about the hard work of preparing for release, needs to take its place.

Few crimes have been as culturally significant as the Manson family’s murders.

Committed in the summer of 1969, they fanned the flames of an already explosive year. That July, humans landed on the moon for the first time. War raged in Vietnam. Black Power ascended within the civil rights movement. Hippies descended onto a Woodstock farm. And Nixon had just begun his tenure in the Oval Office. By the time members of the Manson family killed their first victim, Hinman, in a robbery attempt on July 27, 1969, Angelenos were already on edge.

Writer Joan Didion, then living in Hollywood, was one of them. Despite many carefree moments, “there were odd things going around town,” Didion reported in her essay “The White Album.” “This mystical flirtation with the idea of ‘sin’—this sense that it was possible to go ‘too far,’ and that many people were doing it—was very much with us.”

Hinman’s death didn’t make the Los Angeles Times. But news of the August 9 murders at Tate’s house on Cielo Drive “traveled like brushfire,” Didion remembered. Five victims shot, stabbed, or throttled in what appeared to be a ritualistic mass murder. The murders of supermarket executive Leno LaBianca and his wife, Rosemary, the following day further fueled the hysteria. By the time the final victim, Shea, disappeared on August 25, panic had set in.

From August until the indictments of Manson family members in December, Los Angeles was gripped by the apparently chance sequence of events surrounding the crimes, their terrible violence, and the circus atmosphere of the trial. Didion was not alone in feeling certain that the year’s crimes “did not fit into any narrative I knew.”

Her brother-in-law, journalist Dominick Dunne, made similar observations in his 1999 memoir. “The shock waves that went through the town were beyond anything I had ever seen before,” he wrote. “People were convinced that the rich and famous of the community were in peril. Children were sent out of town. Guards were hired. Steve McQueen packed a gun when he went to [Manson family victim] Jay Sebring’s funeral.”

It’s in the context of these inexplicable crimes that Didion wrote “The White Album” ’s iconic first sentence: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” And out of the fog of fear, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi spun the first significant story around the Manson family, one that recognized our deep societal need for monsters.

“These defendants are not human beings, ladies and gentlemen,” Bugliosi told the jury during the first Tate-LaBianca trial. “These defendants are human monsters, human mutations.”

This interpretation still seems to exert a cultural hold. It appears, notably, in Newsom’s 2019 statement reversing Davis’s parole grant. “Mr. Davis was part of one of the most notorious criminal cults in California history,” it reads. “It is difficult to overstate how impactful these crimes were on the people of California. They left a legacy of terror and pain that continues to haunt the state today.”

Ask anyone on the street whether they can identify a Manson family member by name, and the answer is likely no. But haunting can take many forms. The current one, congealed and reworked by popular culture into a “Manson-industrial complex,” as cultural critic Peter Biskind called it, has produced some 60-odd books, feature films, documentaries, and TV series as well as an opera.

The fresh onslaught of retrospectives delivered by the 50th anniversary of the murders didn’t add much clarity. But they spoke to the continued hold the story has on the American public. Quentin Tarantino’s 2019 film about the Manson era, Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood, with its evocative fairy-tale title and revenge-fantasy ending—in which the bodies knifed and bloodied are those of dirty hippies rather than the beautiful Hollywood elite—did offer one piece of insight. It’s an alternate history that channels the memory of the trauma and a desire for retribution that is difficult to escape.

One of Davis’s first appearances in the public narrative of the Manson family’s crimes occurred on December 3, 1970, when he surrendered outside Los Angeles’s Hall of Justice. A front-page photo in the Los Angeles Times captured the moment as Davis—bearded and barefoot and grinning, with a freshly carved X displayed just between his eyebrows—disappeared into the court building. Fifteen months later, on March 14, 1972, a jury found him guilty of first-degree murder, after 12 days of deliberation. The judge sentenced the 28-year-old to seven years to life in prison.

The story of what led him to surrender at that courthouse was one of the first things I hoped to learn from Davis when I started meeting with him in San Quentin’s common areas, wherever we could find a peaceful spot for conversation. From these talks, and his parole transcripts, a far different picture of Davis emerged.

A Louisiana boy who enrolled briefly at the University of Tennessee before hitchhiking west in his early 20s, Davis worked odd jobs to make ends meet. Wherever he could, he’d rely on his considerable skills as a welder, a trade passed down to him by his father. These skills were the only source of positive memories of an otherwise mean-spirited alcoholic.

For Davis, the 1960s were a time of drug-addled absence, which he looks back on as “aimless, desperate, seeking.” It was in this spirit of disjointed wanderlust that he first encountered Manson at the cult’s Topanga Canyon complex in the spring of 1968—lounging in a tree-shaded antique bathtub with several young women. Davis had been taken there by a mutual friend, and the two stayed for a while, playing music, doing drugs, enjoying the female company. He was immediately attracted to Manson, whom he saw as a charming, talented person with lots of musician friends.

A year later, after some months of traveling, Davis settled in with the Manson family, even as the situation changed from peace and love to something harder. When the group, who otherwise lived off stolen credit cards, decided to try out robbery on a larger scale, Davis played a role as Manson’s driver. Some of the girls got it into their heads that Hinman, a young music teacher who lived nearby in Topanga Canyon, had an inheritance they could take. In late July, the group invaded Hinman’s home with extortion in mind. After days of threats and torture, Hinman was stabbed and died from wounds to the chest.

Davis said he did not know in advance about or participate in the attacks on the Tate and LaBianca households a few weeks later. But he told me that when he found out what his companions had done, it didn’t change his perspective: “It didn’t mean a thing as long as I had what I wanted—sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll.”

He was involved in the death of their last victim, Shea, a general hand at Spahn Ranch, where the family had moved its compound. Manson was convinced Shea was a “snitch.” No one asked questions when Manson organized Charles “Tex” Watson, Steve “Clem” Grogan, Bill Vance, and Davis to get Shea into a car on the pretense of picking up new car parts in town. On the drive, they pulled off to the side of the Santa Susana Pass, an old road between the San Fernando and Simi Valleys, and attacked him in the underbrush. Shea was stabbed by Manson and the others. Grogan delivered the fatal blow. They buried him in late August, near Spahn Ranch. Shea’s body was eventually found with information from Grogan, who described the burial place in return for early release, in 1985.

Davis recalled that during Shea’s murder, he walked away, down the hill and up a creek bed to the ranch. He went into one of the bunkhouses and slept for a long time. But the shock wore off within a few days, and until Manson’s arrest on October 12, 1969, he carried on with life at the ranch. Afterward, Davis hid out with a couple of young women in San Bernardino. Then one morning, he woke up and knew he was going to turn himself in. “That was my first good decision in a long time—I suppose my first step toward rehabilitation, in kind of a left-handed way,” Davis said. “I didn’t realize the implications of it. I just knew that I couldn’t live on the run.

I couldn’t hang out with Davis for long and not cross paths with someone who knew him from California Men’s Colony (CMC), in San Luis Obispo, where he served the majority of his sentence. As a nonchurchgoing person, it didn’t occur to me right away that Davis’s friends view him as an essential presence in their Christian community. Whenever they talk about Davis, they invariably mention his unwavering faith and the impression he’s made on their own religious experiences.

One of them is Derry Brown. Brotha D, as he’s affectionately known, never hesitated to stop whatever he was doing and hug Davis warmly when he saw him. In other prison situations, it’s unheard of for men of different ethnicities and races—in this case, one Black, one white—to display their camaraderie so freely on the yard. But the sincerity of Brown and Davis’s friendship superseded racial boundaries.

Before arriving at CMC in 2001, Brown had heard all the prison rumors about one of Charles Manson’s followers being a pillar of the church, so he knew who Davis was before he got to know him personally. They fellowshipped as brothers, and, Brown told me, “I came to love him as a brother.”

“It’s a trip to juxtapose his journey with Manson’s,” Brown said. “Just the other day, there was some footage of Charles Manson on TV way back before he died, and he just looked so ancient—not at all vibrant and full of life like Bruce. It’s obvious that Bruce’s faith has kept him going strong. That’s why he’s still around.” Brown was close with Davis at CMC and then at San Quentin; he has since been released on parole.

It’s true that Davis is one of San Quentin’s most visible elderly residents. Before his latest hip replacement surgery, in September 2021, he made it a point to come out to the yard for a few hours each day to conduct impromptu Bible studies. Sometimes he’d sit on an upside-down five-gallon plastic bucket with a worn woolen blanket folded on top, surrounded by handfuls of men, some he’d known for years and others he’d only just met. The sloped length of faded asphalt overlooking the yard became his pulpit. Beside him lay his drab aquamarine guitar case and his state-issued mesh laundry bag, in which he transported his treasured leather Bible.

Other times—depending on the weather and San Quentin’s yard schedule—Davis stood alone, strumming his guitar and rasping serenely. “The Lord has got my back,” went the signature verse of his own original song. “The Holy Ghost is pulling my slack.… The Devil had me down. And Jesus is putting my feet on solid ground.”

For many who spend time with Davis, his faith is what matters. Roberto Morales, for one, did not know who Davis was when he caught one of his sermons at CMC in 2013. But Morales liked what he heard and signed up for Davis’s Bible study curriculum.

“It was the first time in my life I was meeting an authentic Christian,” Morales, who is now at California State Prison, Corcoran, said. “A man who’s lived his faith. He lives and breathes Jesus Christ. And he has this quiet sense of dignity, very unassuming. To me, he’s just a friend. I can’t imagine him being involved [with the Manson family].”

Nearing the end of the base term of his 35-years-to-life sentence, 65-year-old Morales is facing his own BPH hurdles as a three-striker struck out on burglary charges. When he walked side by side with Davis on mild sunny mornings, their bright smiles and conversation seemed almost out of place along the dusty cement track. Somehow, Morales’s broad six-three, 225-pound frame never dwarfed Davis.

“He’s like this little hillbilly gnome, but you cannot avoid being impacted by him,” Morales said. “He’s helped me realize the transcendence of the Christian journey.”

He considers Davis’s repeated BPH denials morally unconscionable.

“It’s so sad,” Morales said. “There’s a lot of men like Bruce in prison. They just want to go fishing, go feed the pigeons in the park. We give lip service to rehabilitation, but the idea of redemption—that’s a whole different ball game there. God’s honest truth—I’d do five more years in prison if they’d just let Bruce go.”

Davis has been parole-eligible since 1977. He first went before the BPH in 1978. His parole was denied. The same thing happened in 1981, 1982, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008.

Then the unexpected occurred. He was found suitable for release in 2010, a decision subsequently vetoed by then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. The same process—the board grant, the governor veto—took place again in 2012, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2021.

The number of times Davis has gone before the board is rare. His need to go is not. The opportunity for parole is a reality for the majority of the people convicted of felonies in the United States. According to the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit working for decarceration, most states make use of indeterminate sentencing. Of them, California holds the largest lifer population, around 30 percent of the state’s total prison population.

Parole hearings are a tough hurdle, and with the additional obstacle of the governor veto in California, historically, few have managed to clear it. Until 2008, the number of prisoners found parole-suitable by the BPH remained below 8 percent, while the gubernatorial-reversal rate was high, between 70 and 100 percent.

Then the Supreme Court of California intervened, deciding in the landmark 2008 case re Lawrence that the BPH and the governor must provide “some evidence” of a prisoner’s current dangerousness beyond the original crime to justify parole denial. Thanks to another case decided that same year, re Shaputis, the nature of that evidence can be vague; a “lack of insight” could be enough to constitute a threat to the public.

Still, the number of lifers who have been paroled has steadily increased. The board released 1,201 life prisoners in 2020, its highest number ever. More than 10,000 lifers have been released since re Lawrence.

The BPH is made up of 21 full-time, governor-appointed commissioners and dozens of deputy commissioners who serve as civil servants. Working in pairs, one commissioner and one deputy commissioner preside over a parole-suitability hearing, which proceeds in an interview-like fashion over the course of several hours. In addition to the commissioners, the prisoner, and their attorney, a few others may be present—a representative from the district attorney’s office, victims or their representatives, and, in limited circumstances, members of the media.

Parole hearings are not trials. They do not introduce new evidence. They do not relitigate crimes. They are not supposed to dwell on the nature of the crime or what gets referred to as “unchanging historical factors.” Rather, their purpose—set by re Lawrence and re Shaputis—is to assess how prepared a prisoner is to reenter society.

Parole hearings are, however, a deeply narrative process. And, as in trials, there are often two stories vying for control. One is the story of rehabilitation presented by the prisoner. And the other is what UC Law San Francisco professor Hadar Aviram refers to in her book Yesterday’s Monsters: The Manson Family Cases and the Illusion of Parole as the “moral memory” of the crime, contained in the statements from victims or their representatives and the district attorney’s office.

In Davis’s case, this other set of narrators includes a member of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office and victim representatives, who entered the BPH process in 2012. Debra Tate, a younger sister of Manson family victim Sharon Tate, began appearing as a victim representative of the Hinman family at Davis’s hearings after he was first found suitable for parole.

Since re Shaputis, success with the BPH largely hinges on a prisoner’s ability to demonstrate “insight” into their crime. In other words, what matters is how coherently a person can explain the circumstances of their crime, how genuinely they can express remorse, and how fully they can present a transformed version of themselves. As Aviram makes clear, it’s a subjective assessment based significantly on the interview performance.

The first time Davis was recommended for parole, the level of detail he offered in his story seemed to be a deciding factor. In his decision, presiding commissioner Robert Doyle said that Davis articulated a level of insight that “didn’t happen overnight.… It was a slow comer.”

From that hearing forward, his ability to delineate pivotal moments kept the parole grants coming. Over the years, Davis has reflected on a difficult relationship with his father. Then there was his decision to become sober in 1974, while at Folsom State Prison, which opened him up to a whole new world of emotions. He’s also talked about witnessing the murder of a young Black man in prison around the same time. Looking at that youth covered in blood, Davis told me during one of our long talks, “all of a sudden, I realized what I’d done, and I knew that I really deserved to be in prison.”

For Davis, though, the most profound moment in his story was his conversion to Christianity the same year he became sober. An inner voice told him to look out at the yard. Everyone in Folsom’s recreational area suddenly transformed into images from a dark and eerie end of days. “They were cloaked with death. It really frightened me,” Davis said. “When that light came on, it showed all my dirt. It exposed me.” Believing he deserved to die for his sins, he threw his hands up to the heavens and gave himself over to the Lord.

In the years following, Davis studied and embraced the Bible. He found a home in the Christian church at CMC and eventually earned a doctorate in theology from Bethany Theological Seminary. For his dissertation, Davis wrote “Spiritual Manual for Maturing Christians,” a curriculum of 10 chapters that he has taught to others ever since. It includes sections called “Your Future: Picture It” and—with unintentional irony—“Re-entry: Returning to Society.”

The problem with paying so much attention to insight during parole hearings, critics point out, is that too much emphasis falls on emotion and introspection and not enough on measurable criteria, like professional and therapeutic development, which have been the cornerstones of the California prison system’s correctional approach since 2005.

Davis is a textbook example of the rehabilitated prisoner. He’s had no disciplinary write-ups since 1980, and his in-prison vita reflects an exceptional work ethic. Over the past 50 years, Davis has held down a huge range of jobs—as an operator in a printing plant, a clerk, a building orderly, a porter, a culinary department runner, a teacher’s aide, and an instructor.

In addition to the Bethany doctorate, he’s graduated from drafting and steel-welding programs, and he’s taken academic courses through Pennsylvania State University, Ohio University’s Patton College of Education, and Berean School of the Bible. He’s made his way through Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, the Alternatives to Violence Project, and Yokefellows, a faith-based peer-counseling group. He’s undergone Gestalt therapy, guided imagery therapy, psychotherapy, rational emotive behavior therapy, transactional analysis, and stress management and relaxation training.

To get a sense of just how much programming this is, consider the closing remarks of Davis’s lawyer, Michael Beckman, during the 2010 parole hearing: “When my client asked what he could do to make himself more ready for parole, Commissioner [James] Davis [the previous presiding commissioner] did not—because he could not—give him an answer.”

Beckman, an L.A.-based attorney who’s been focused on parole law since 1985, represented Davis for 17 years, first under state appointment and then pro bono. During this time, he became more outspoken about the rationale for keeping Davis in prison, even comparing the parole board’s actions to vigilantism. Beckman has made the case again and again that the governor’s continued reversals convert a sentence of life with the possibility of parole into a sentence of life without the possibility of parole.

“As held by the California Supreme Court in re Dannenberg, no prisoner can be held for a period grossly disproportionate to his individual culpability for the commitment offense,” Beckman pointed out at Davis’s 2017 hearing. “Such excessive confinement violates the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the California Constitution.”

In 2019, Beckman put it in plainer terms: “My client is a political prisoner at this point, plain and simple.”

The presiding commissioner that year, Arthur Anderson, came to a similar conclusion. In his decision to grant Davis parole, he reasoned, “The Supreme Court says after a long period of time, immutable factors such as this commitment offense, prior criminality, unstable social history may no longer indicate a current risk of danger in light of a lengthy period of positive rehabilitation.… Well, we must do the right thing and follow the law because if we don’t follow the law, why have a law?”

Commissioner Deborah San Juan, who presided over Davis’s parole hearing in January 2021, led with an effort to speak directly to the concerns raised in the governor’s veto. Her interview went point by point through Newsom’s objections, in search of concrete answers. She and deputy commissioner Neal Chambers found Davis suitable for release, citing as special considerations his age, his long-term confinement, his diminished physical condition, and, as San Juan told Davis, his ability to be “open and honest and understanding of what your actions caused.”

The sticky issue of notoriety still came up. Chambers voiced concern about potential post-parole challenges related to Davis’s fame and asked him explicitly about his plans to speak or write a book about his crime.

Davis’s answer? “When I speak from a pulpit to a religious group, obviously I want to tell them what Jesus did for me. The caveat is I will never talk about my case except to just admit it,” he said. “My message to them is the message of redemption by Christ through his grace. That’s the message.”

Yet Newsom reversed that BPH decision, too.

On July 8, 2022, Davis went before the board again. This latest hearing inserted a new twist into his story. The assigned commissioners, Julie Garland and Rachel Stern, denied his parole, after more than a decade of grants by their colleagues. Nothing had changed in Davis’s vita. Still, the commissioners saw in Davis’s story a minimization of personal responsibility and, as Garland put it, a lack of “change, growth and maturity.” They also perceived his ability to tell his own story as a threat, even in a religious context.

Commissioner Garland explained that she was concerned about Davis’s “willingness to speak to church groups or others about your, as you call it, redemption.”

“You are notorious,” she continued. “The potential impact of you speaking about yourself and your past and your involvement with the Manson family could not only affect the victim’s family, which it clearly would, but it could impact public safety and that others may be inspired to follow a similar path as you.… Our concern is this idea that you want to talk about redemption cannot be disconnected from your involvement with the Manson family.”

Davis’s next hearing is scheduled for January 18, 2024.

What recourse exists for Davis, and for other lifers who face regular parole denials or reversals?

We reached out to the BPH for comment; the press office provided us with the general guidelines outlined for the parole board commissioners from the California Code of Regulations, title 15, section 2281, but no additional solutions.

The legal experts we consulted had more to say. Heidi Rummel, a USC Gould School of Law clinical professor of law and a co-director of the Post-Conviction Justice Project, pointed out that the remedy can come from the courts. “There is a due process liberty interest in parole in California, which is unusual. Most states don’t have that,” she said. Re Lawrence found that if the governor or the board does not offer a sound legal basis for denying parole, that decision can be overturned by a court. Judicial review has played an important role in shifting the emphasis in parole board decisions to genuinely assessing risk and rehabilitation.

This solution did, in fact, work recently for another Manson family member, Leslie Van Houten. Like Davis, Van Houten was sentenced to seven years to life for murder. She went before the BPH successfully five times, only to have her parole grant reversed each time by California governors. Her lawyers challenged the vetoes before a California Court of Appeal, and in May 2023, the judge ruled in Van Houten’s favor. She was released in July.

Beckman would like to see the review standard tightened to something more concrete than “some” evidence, at the very least when it comes to the governor’s review. “An improvement would be requiring a preponderance of the evidence, with current datasets of clear and convincing evidence to overturn [the board’s decision],” he said.

California could also choose to get rid of the gubernatorial veto, which often incentivizes the politicization of crimes and parole. That’s just one of several suggestions Aviram lays out in Yesterday’s Monsters. There is room for other institutional changes as well.

A big step forward would be to diversify the BPH, which has traditionally been heavy on former law enforcement officers and former prosecutors. Aviram recommends adding people with backgrounds in social work and those with firsthand experience being incarcerated as a way to correct for the confirmation bias and tunnel vision that can come from a shared professional background.

“If parole is really designed to protect society, the preoccupation with the symbolic meaning of the crime of confinement, especially decades after the fact, is inappropriate,” Aviram writes in Yesterday’s Monsters. “The protection of public safety, as well as the wise and prudent expenditure of public funds, should lead the hearings to focus on whether inmates might commit future crimes, not on moral judgements about their virtues and flaws.”

Some of these changes have been proposed in a new piece of parole-reform legislation, California Senate Bill 81, introduced by Senators Nancy Skinner and Josh Becker on January 12, 2023. The bill would require the BPH to cite more objective criteria for denial, including a “preponderance of the evidence,” and it would put in place a more robust oversight process. (On October 8, shortly before we went to press, Newsom vetoed the bill.)

Until 2022, every time the BPH found Davis suitable for parole, he waited patiently to see what would happen to him. He once learned that Governor Jerry Brown had vetoed the decision when another prisoner at CMC saw the story on the TV news and offered their condolences. Davis has held off on undergoing hip replacement twice, awaiting the outcome of a pair of hearings. But he went ahead with the latest surgery after the latest veto. As he stepped gingerly around San Quentin post-replacement, his friends and Christian brothers prayed that the system would let Davis go next time.

The attention paid to him by those around him is never lost on Davis. He’s humbled by his status as a respected elder figure within the community. Whether in casual talks while limping around the yard or in one-on-one theological discussions or in the center of a group Bible study, Davis believes he’s serving his best purpose in the here and now.

Despite the successful hip replacements and the bout with COVID he survived—the ever-youthful glimmer in Davis’s eyes notwithstanding—I see an increased fragility in him. California Correctional Health Care Services can do only so much for so long. I’ve never discussed mortality with him directly, other than to ask, “How are you feeling? How’s it going?” To which he always replies, “Fine. Great,” before launching into talk of spiritual eternity.

The last time I spoke to Davis, shortly after his most recent BPH denial, he had begun focusing instead on a different kind of story, one written down and printed in a small pamphlet during his CMC days. He arrived at San Quentin with bulk copies of this “tract,” as he calls it—a testimonial he gave out freely until they were almost gone. He now hoped to get an updated and improved version printed. It seemed to be extremely important to him. Perhaps his health and age were spurring him to put his words down in print, to focus his narrative energies on his epitaph rather than on his interviews before the board.

While Davis worked on his document, the conversation on rehabilitation in California took a politically progressive turn. Last spring, Newsom visited San Quentin to announce a bold plan—a transformation of the prison into a new kind of facility focused on rehabilitation, education, and job preparation. According to the vaguely proposed design, a “center for innovation” might occupy the space currently used by death row and the Prison Industry Authority warehouse. With this center, Newsom said, “we take the next step in our pursuit of true rehabilitation, justice, and safer communities through this evidenced-backed investment, creating a new model for safety and justice—the California Model—that will lead the nation.”

For this model to work effectively, it will not only require the facade of transformation at California’s oldest prison. It will also require a concerted effort to change the hearts and minds of the public, who will have to give up their monsters to make room for a new vision of rehabilitation. It’s an invitation to cast aside cynicism and to dream of a legal system that lives up to its restorative potential. It might even be possible to imagine a new chapter to the narratives of lifers like Davis. It’s a pie in the sky for now, but maybe one day soon it will be a more fitting ending to this story of justice and incarceration. To be continued…•

Monday, December 18, 2023

Seldom Seen Charlene

I ran across this picture of Charlene Cafritz in a newspaper archive. I had to fiddle with the brightness to bring her face out so the rest of the image is washed out. I don't think we have seen any pictures of Charlene during the Manson years. She looks healthy in this picture.

Monday, December 11, 2023

The Hatfield's, McCoy's and Charlie Manson

Fred and Sheila McCoy from the Hatfield and McCoy Museum Adventures go on a road trip to stop by some Charles Manson related locations in Kentucky. Fred also explains how Manson is related to the McCoy's which as near as I could tell from Fred's wandering report means that he is also distantly related to Manson.

Honestly, the video is way too long for the information given and might be best viewed behind a couple of fingers of good ole Kentucky whisky, by the end I found Fred and Sheila to be absolutely endearing. They have undaunting energy. * Spoiler Alert * Fred really, really does not like Devil Anse Hatfield.

Monday, December 4, 2023

Scratch

Scratch is a term that law enforcement uses for the notes that they take. They are informal and much like the notes and lists we make for ourselves, they can be on a variety of different types of paper written with whatever writing implement we have handy, with our own abbreviations.

Some of the notes in the pdf are hard to read and decipher, I haven't quite figured all of them out. The notes do offer a look at the steps LE takes to develop leads to further the investigation. Not all leads pan out and some are bogus.

I will be posting the scratch over the next few weeks in small batches. If you look at it all at once, it's just too overwhelming.

On page 20 of the file there is mention of Bill Vance and Topanga Stables, it's something about a car given to the owner of the stables and Bill wanting the car back so he can start a church as near as I can tell.

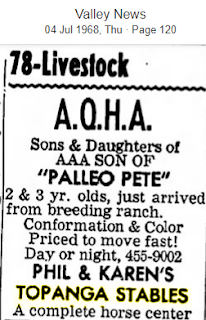

I did a search on Topanga Stables and found that Phil and Karen Schoonmaker owned it. In 1968 there were ads in the local newspaper for horses that were for sale at the stables.

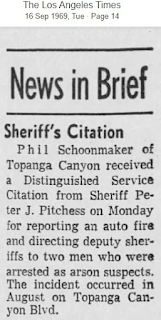

In September of 1969 Phil Schoonmaker received a Distinguished Service Citation from LASD for aiding in the arrest of arsonists.

Topanga Stables was a place where the public could go on trail rides much like Spahn Ranch. This is a portion of an article about the different places to go trail riding in LA.